Regency Dancing

Part of the Articles series.

Written by Rose.

Dancing was a very important part of Regency society and the courtship process because it was pretty much the only time young men and women could converse with each other, look into each other's eyes and hold each other's hands without the presence of a chaperone. However, like most aspects of Regency society, dancing was intensely rule bound. Every dance would be watched hawk-eyed by those too 0ld to dance and balls were a hotbed of incipient scandal and bad behaviour by those who so much as poked one toe out of line.

This essay does not attempt to explain exactly what dances they would have danced and how to dance Regency dances, nor what to expect at Almack's, but to provide some basic guidelines on how characters would be expected to behave at any ball.

Summary of essay for those who don't want to read it all:

- Men ask, women accept.

- A woman cannot dance again having refused a partner.

- Dancing more than twice with the same partner equalled an official engagement.

- No more physical contact than touching hands or an occasional hand on waist.

Terminology

- Dances were in groups of two.

"Then, the two third he danced with Miss King, and the two fourth with Maria Lucas, and the two fifth with Jane again, and the two sixth with Lizzy, and the Boulanger--"

Pride and Prejudice

"“I take this opportunity of soliciting [your hand], Miss Elizabeth, for the two first dances especially”"

Pride and Prejudice

- To dance with someone is to stand up with them.

"“I was so vexed to see him stand up with her”"

Pride and Prejudice

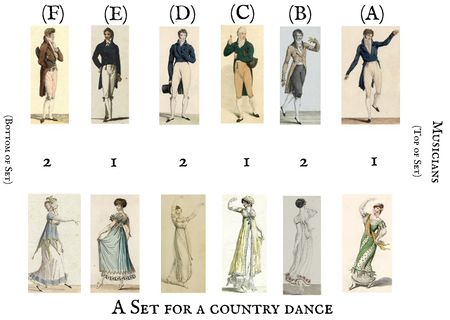

- One danced in a set, which was a line of partners, men facing women. Large balls might have more than one set per dance, depending on the number of couples. Sometimes a set just consisted of three or four couples, who danced in a square or rectangle with members of this group alone. Friends might choose to dance next to each other in the set. Sets of four or eight people in a square were known as quadrilles, and the first quadrille was danced in Almacks in 1816, although it had been danced at private balls before that.

“…nothing, she declared, should induce her to join the set before her dear Catherine could join it too. "I assure you," said she, "I would not stand up without your dear sister for all the world; for if I did we should certainly be separated the whole evening."”

Northanger Abbey

Note also the use of the term 'stand up with'.

- Dancers would move down the set as the dance progressed. The most importance place to start the dance would be as the couple at the top of the set. The top position of the first dance was the most important place of the whole ball. This would generally be reserved for the hostess of the ball, the person of the most consequence or, if it was given in a particular person’s honour (say a private ball for a debutante), that person. They would open the ball and the set would not form before this person and their partner had taken their places. It was a great honour. The top couple would set the style of the dance which the rest of the set would then copy.

“Sir Thomas brought him to her, saying something which discovered to Fanny, that she was to lead the way and open the ball; […]and she found herself the next moment conducted by Mr. Crawford to the top of the room, and standing there to be joined by the rest of the dancers, couple after couple, as they were formed. She could hardly believe it. To be placed above so many elegant young women! The distinction was too great.”

Mansfield Park

“It had just occurred to Mrs. Weston that Mrs. Elton must be asked to begin the ball; that she would expect it; which interfered with all their wishes of giving Emma that distinction.”

Emma

- A lady would carry a card listing all the dances available and whenever she was asked to dance she would fill in the space with her partner’s name.

Rules

- The man would ask the woman to dance. As in marriage, the woman only had the power of refusal.

- If a woman refused one man she could not then accept another man. To do so would be unpardonably rude. Refusing one partner without excuse was tantamount to declaring an intention not to dance for the rest of the evening.

"“Well, Miss Morland, I suppose you and I are to stand up and jig it together again."

"Oh, no; I am much obliged to you, our two dances are over; and, besides, I am tired, and do not mean to dance any more.”"

Northanger Abbey

- However, if a lady was indisposed and did not want to dance, she might remain with her partner for that pair and talk with him.

- Once a dance had begun, no couple could change partners or leave the set, apart from out illness.

- Dancing two pairs of dances with the same person in one evening signaled a serious interest in the woman and was liable to be talked about. Dancing three or more pairs was only permitted between engaged couples.

"“He wants me to dance with him again, though I tell him that it is a most improper thing, and entirely against the rules. It would make us the talk of the place, if we were not to change partners.”"

Northanger Abbey

- For the duration of the dance the partners would belong to each other and it could be considered rude to come between them.

“Her partner now drew near, and said, "That gentleman would have put me out of patience, had he stayed with you half a minute longer. He has no business to withdraw the attention of my partner from me.”"

Northanger Abbey

- The dancing was generally the affair of younger people. Parents and chaperons and sometimes married people would watch on the sidelines. There would generally be a card room adjoining the ball room for those who did not intend to dance.

- A ball would include at some point a supper break.

- Masquerades were a popular type of private party. Everybody would come in fancy dress costume and much fun was to be had in guessing who was who. It provided a chance to do something potentially scandalous without being discovered. Popular choices included the following:

“Dominos of no character, and fancy dresses of no meaning, made, as is usual at such meetings, the general herd of the company: for the rest, the men were Spaniards, chimney-sweepers, Turks, watchmen, conjurers, and old women; and the ladies, shepherdesses, orange girls, Circassians, gipseys, haymakers, and sultanas.”

Cecilia

Common Misconceptions

- The final edition of The Dancing Master by John Playford (and later his son Henry) was last published in 1728 and such dances as are often in Regency films are very outdated by 1811.

- Dances were danced not gracefully walked- it was a strenuous exercise!

- No waltzes! The waltz was not introduced in London until 1816 and was considered scandalous (even for Lord Byron).

“So long as this obscene display was confined to prostitutes and adulteresses, we did not think it deserving of notice; but now that it is attempted to be forced on the respectable classes of society by the civil examples of their superiors, we feel it a duty to warn every parent against exposing his daughter to so fatal a contagion.”

Editorial in The Times newspaper

- There would have been no dances in which man and women clasp each other. The most contact they would have would be holding hands. However, sometimes dances forced the couple to approach very close to each other without touching. There were plenty of flirting opportunities. After all, dancing was pretty much the only opportunity for young men and women to be “alone” together without a chaperone.

- Regency dances were not dances in which partners danced with each other alone. Many dances would involve dancing with the people standing on each side of yourself and your partner. It was very sociable.

- There was a lot of standing around during the dancing, especially when waiting at the bottom/top of the set depending on the number of couples. This explains why so many conversations take place when dancing in books.

- For example, a dance move might go as follows (men: letters; women: numbers):

A 1

B 2

C 3

B3 dance a step then C2 while A1 waits. Then B2 goes round A1, moving up the set. The positions now are as follows:

B 2

A 1

C 3

Then A3 and C1 repeat the steps while B2 waits. And so on.

- Sometimes the set divided into smaller sets of dancers so that only two or three pairs would ever dance together.

- It’s very possible that a debutante’s first ball will be the first time she has ever danced with a man, as opposed to with schoolgirls, let alone touched their hand!

Suggested reading

- The first half of Northanger Abbey is filled with Bath ball scenes, all of which are very instructive and entertaining. The best chapter to read is probably Chapter 10 in which Henry Tilney compares dancing to marriage, outlining the comparative duties of both.

- Evelina, Letter 11 is a good guide of how not to behave at a London ball. Evelina, a naïve debutante, manages to run away from the dancing, refuse one partner and accept another, laugh in a man’s face and generally behave badly without trying. The rules were very strict.

- Mansfield Park contains a private ball in Fanny’s honour. Read Chapter 28.

- It was very easy to slight people at a ball if one chose to be rude. Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 3 and Emma, Chapter 38 contain two of the most famous in literature.

- Cecilia contains a detailed account of a masquerade ball in Volume 1, Book 2, Chapter 3.

- The most famous ball in literature is probably the Netherfield Ball in Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 18.

On Film

Dances in period drama adaptations tend to have the following faults:

- Dances are often too old.

- Dances are walked, not danced.

- Dances are cut so couples are seen to be doing more dancing than they would have been.

However, Darcy and Elizabeth’s dance at Netherfield is a good dance to watch. Notice (1) how the end couple has to wait in places because there is an odd number of couples; (2) how alternate couples have to stand still some of the time (they would have done so more than is shown in this adaptation); (3) how Darcy and Elizabeth move down the set; (4) the repetitive nature of the dance.[1]

The 2009 adaptation of Emma, starring Romola Garai and Jonny Lee Miller, shows just how active and strenuous Regency dances were.

Also see the beginning of this video for a good example of a different type of dancing.[2]

Author's Note: I don’t like the adaptation as a whole, however.

Other References

Capering & Kickery[3]

An excellent site on Regency dance.