British Museum

The British Museum was established in 1753, largely based on the collections of the physician and scientist Sir Hans Sloane. The museum first opened to the public on 15 January 1759, in Montagu House, on Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury, where the museum and its collection have remained since.

The British Museum was originally founded as a "universal museum". During the course of his lifetime Sloane gathered an enviable collection of curiosities and, not wishing to see his collection broken up after death, he bequeathed it to King George II, for the nation, for a sum of £20,000.

At the time of his death, Sloane's collection consisted of around 71,000 objects of all kinds including some 40,000 printed books, 7,000 manuscripts, extensive natural history specimens including 337 volumes of dried plants, prints and drawings including those by Albrecht Dürer and antiquities from Sudan, Egypt, Greece, Rome, the Ancient Near and Far East and the Americas.

On 7 June 1753, King George II signed into being the Act of Parliament which established the British Museum. The British Museum Act 1753 added two other libraries to the Sloane collection, which were joined in 1757 by the "Old Royal Library", now the Royal manuscripts, assembled by various British monarchs.

The British Museum was the first of a new kind of museum – national, belonging to neither church nor king, freely open to the public and aiming to collect everything. Sloane's collection, while including a vast miscellany of objects, tended to reflect his scientific interests. The addition of the Cotton and Harley manuscripts introduced a literary and antiquarian element and meant that the British Museum now became both National Museum and library.

From 1778, a display of objects from the South Seas brought back from the round-the-world voyages of Captain James Cook and the travels of other explorers fascinated visitors with a glimpse of previously unknown lands. The bequest of a collection of books, engraved gems, coins, prints and drawings by Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode in 1800 did much to raise the Museum's reputation; but Montagu House became increasingly crowded and decrepit and it was apparent that it would be unable to cope with further expansion.

The museum's first notable addition towards its collection of antiquities, since its foundation, was by Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803), British Ambassador to Naples, who sold his collection of Greek and Roman artefacts to the museum in 1784 together with a number of other antiquities and natural history specimens. A list of donations to the Museum, dated 31 January 1784, refers to the Hamilton bequest of a "Colossal Foot of an Apollo in Marble". It was one of two antiquities of Hamilton's collection drawn for him by Francesco Progenie, a pupil of Pietro Fabris, who also contributed a number of drawings of Mount Vesuvius sent by Hamilton to the Royal Society in London.

The Reading Room

The Museum also housed a Reading Room, which eventually became the basis for today's British Library

“Such literary gentlemen as desire to study in it, are to give in their names and places of abode, signed by one of the officers, of the committee; and if no objection is made, they are permitted to peruse any books or manuscripts which are brought to them by the messenger, as soon as they come to the reading room, in the morning at nine o’clock; and this order lasts six months, after which they may have it renewed. There are some curious manuscripts, however, which they are not permitted to peruse, unless they make a particular application to the committee, and then they obtain them; but they are taken back to their places in the evening, and brought again in the morning.”[1]

The Collections

By 1809, the Museum's collection was arranged thus:

- Lower floor: Library of printed books

- Upper floor: modern works of art; manuscripts; minerals; shells, fossils & herbals; insects, worms, corals & vegetables; birds & quadrupeds, stuffed; quadrupeds, snakes, lizards, and fishes, in spirits.

- Gallery: terra cottas; Greek & Roman sculptures; Roman sepulchral antiquities; Egyptian antiquities; coins & medals; Sir William Hamilton’s collection; drawings & engravings.

By 1811, the year the LL is set, the exhibits included:

The museum’s collections included:

- The Cottonian library of books and manuscripts (early 1750s)

- The Harleian collection of manuscripts (early 1750s) – purchased by Parliament for £10,000

- The first ancient Egyptian mummy (1756)

- Various ethnographic artefacts from Captain Cook’s Pacific voyages, including a Tahitian mourner’s dress (1756)

- The “Old Royal Library” of the sovereigns of England – donated by George II (1757)

- The trunk of a tree gnawed by a beaver (1760)

- A stone resembling a petrified loaf (1760)

- Italian antiquities (1762) – £8410

- A live tortoise from North America (1765)

- Gustavus Brander’s fossils (1765)

- Birch’s library (1766)

- Greenwood birds – from Holland (1769) - £460

- Sir William Hamilton’s collection of Greek vases (1772) – Etruscan, Grecian and Roman antiquities - £8400

- Halhed’s oriental manuscripts (1796)

- Hatchett’s minerals (1798) - £700

- Tysson’s Saxon coins (1802)

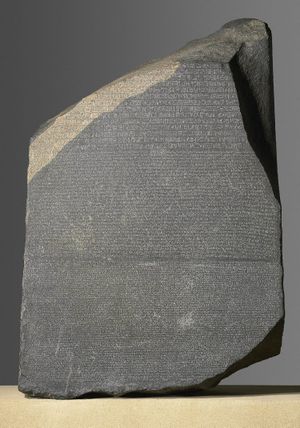

- The Rosetta Stone (1802)

- The Townley collection of classical sculpture including the “Discobolus” statue and the bust of a young woman “Clytie” (1805)

- Lansdown manuscripts (1807) - £4925

- Bentley’s classical library (1807)

- Roberts’ coins (1810)

- Greville minerals (1810) - £13727

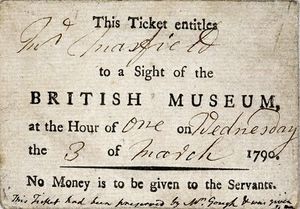

How to Visit

Entry was free and granted to “all studious and curious Persons”.

The 1800 guidebook describes the admission process:

“Those who come to see the curiosities, are to give in their names to the porter, who enters them in a book, which is given to the principal librarian, who strikes them off, and orders the tickets to be given in the following manner: In May, June, July and August, forty-five are admitted on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, viz. fifteen at nine in the forenoon, fifteen at eleven, and fifteen at one in the afternoon. On Monday and Friday fifteen are admitted at four in the afternoon, and fifteen at six. The other eight months in the year, forty-five are admitted in three different companies, on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, at nine, eleven and one o’clock.” (1)

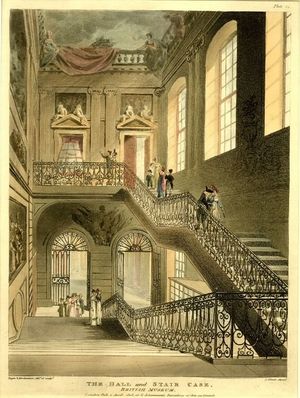

According to the British Museum’s website, visitors were taken round the exhibition by an under-librarian in groups of five, up the great staircase, through the upper rooms and down again to the ground floor.

A guidebook for 1803-4 says:

“All fees are prohibited, and persons who wish to view the Museum must previously enter their names and address, and the time when they would wish to see it, in a book kept by the porter. On a future day they will be supplied with tickets free of expense. Children are not admitted.

The British Museum in LL

On Monday the 21st May, Kenward Asquith and Honoria Bartram made an excursion to the Museum

Further Reading

British Museum: About Us - The Museum's Story Regency History: The History of the British Museum

- ↑ From Scatcherd's Ambulator (1800)