Peninsular War: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

This article is a work in progress. | This article is a work in progress. | ||

''Article by [[ | ''Article by [[Sharpie]]'' | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Revision as of 15:20, 21 January 2017

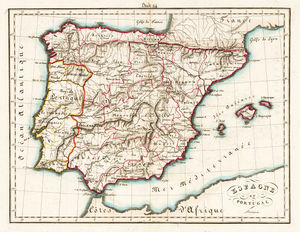

The Peninsular War (1808-1814) was the major theatre of war between Britain and Napoleonic France after was declared with Napoleon in 1803 after the Peace of Amiens. As London Life is set in 1811, with current threads taking place in May, this page will only go up to the Battle of Albuera (16th May 1811) news of which which was not reported in London until the end of May

This article is a work in progress. Article by Sharpie

Background

In 1807, France and Spain were still allies, although somewhat reluctantly so on the part of Spain, and armies of both nations occupied Portugal which was a British ally. In November 1807, the Portuguese royal family fled to Brazil, then a part of the Portuguese empire. In 1808, Napoleon set his brother on the Spanish throne, deposing and imprisoning the Spanish king Charles IV, and the Crown Prince, Ferdinand. This led directly to the uprising of the 'Dos de Mayo', the Second of May.

The Peninsular War itself consisted mainly of pitched battles between the British and French armies, and a guerilla warfare conducted by Spanish irregulars – it was this that introduced the term 'guerilla warfare' to the English language. This 'little war' (a translation of the Spanish word guerilla) was so effective that by 1813, a single French officer carrying a despatch had to be accompanied by a whole cavalry squadron for his own protection, whereas the British Exploring Officers could ride alone and unaccompanied in full uniform, even behind enemy lines.

The first British forces arrived in Portugal in August of 1808 with Sir Arthur Wellesley in command. On the British march north, the first clash between armies occurred, between a detachment of the 95th Rifles and French pickets at Brilos[1]. The battles of Roliça[2], on the 17th of August, and Vimeiro[3], mere days later on the 21st, while British victories, led to the controversial Convention of Cintra. The Convention allowed the defeated French army of Portugal under Marshal Jean-Andoche Junot to return to France aboard ships of the Royal Navy, with all of their arms, baggage, and personal belongings[4].

Public reception of the Convention was decidedly negative and a military inquiry into the whole affair reluctantly approved and accepted the Convention’s articles. This same inquiry required the three generals responsible for the Convention to be in London, leaving the British army in Portugal in the capable hands of Sir John Moore. Moore took the army into Spain[5], making it as far as Madrid before being forced to retreat back to Portugal. The famous Retreat was made through a harsh Spanish winter and ended with the British making their last stand with their backs to the sea at Corunna[6]. The pursuing French were held off long enough for the British army to be evacuated by the Royal Navy[7].

Sir Arthur Wellesley returned to Portugal in the spring of 1809. The first battle of the renewed Peninsular campaign was fought at Oporto as the British marched north, the same as they had done the previous year. The British advance continued until July when the army reached Talavera de la Reyna. On the 27th and 28th July, the French made repeated attacks on the allied lines, but were repulsed each time. The British losses were 'very large indeed'[8], numbering more than 5,400 officers and men killed, wounded, and missing[9]. By contrast, the French suffered more than 7,000 casualties - many of these were wounded men unable to escape the grass fires on the Cerro de Medellin.

The Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro

The battle of Fuentes de Oñoro was an affair that lasted three days, from the 3rd to the 5th of May, 1811. The French, under the command of Marshal Masséna, opened the battle by advancing on the village of Fuentes de Oñoro itself. This force was comprised of ten battalions of infantry, yet it was not strong enough to capture the entire village. In fact, it was pushed back by a stiff British counter-attack made by only three battalions. The village was the scene of fighting all day. The French made several attempts to capture the village but they were frustrated by a 'most gallant'[10] defence overseen by Lieutenant Colonel Williams of the 60th Rifles.

Both sides spent the following day sorting out their lines, collecting their wounded and dead, and in Masséna's case, laying plans for a fresh attack on the 5th. The French opened their attack shortly after dawn, carrying the village of Posobello at point of bayonet and pressing an assault against the right side of the British line. A charge was made by the Spanish guerrillas, under the command of Julian Sanchez, and was thoroughly routed. In the village of Fuentes de Oñoro itself, the fighting see-sawed back and forth much as it had on the 3rd. "Every street, and every angle of a street, were the different theatres for the combatants; inch by inch was gained and lost in turn... our Highlanders lay dead in heaps, while the other regiments, though less remarkable in dress, were scarcely less so in the numbers of their slain."[11]

Fuentes de Oñoro was in French hands by midday. The battle had been raging for many hours and the British situation was desperate. Lieutenant Colonel Wallace of the 88th Foot was ordered to take his regiment forward to relieve the battered Highlanders and Riflemen. With cool purpose, the Connaught Rangers advanced with bayonets fixed and drove the French from the village. Within two hours, the fighting had subsided. Grattan observed that "towards evening the firing ceased altogether, and it was a gratifying sight to behold the soldiers of both armies, who but a few hours before were massacreing[sic] each other, mutually assisting to remove the wounded to their respective sides of the river."[12] He gives the total loss to both armies as 8,000 men[13] but this is an overestimation. The British suffered a little more than 1,500 wounded and killed, while the figures for French losses vary between 2,100[14] and 4,500[15].

Further Reading

Web Links

Books

Fletcher, I. Galloping at Everything: The British Cavalry in the Peninsular War and at Waterloo: A Reappraisal, Spellmount, 1999

<references>

- ↑ Elizabeth Longford - Wellington: Years of the Sword, p. 149

- ↑ http://www.napoleon-series.org/military/virtual/c_rolica.html

- ↑ http://www.britishbattles.com/peninsula/peninsula-vimiero.htm

- ↑ http://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/diplomatic/c_cintra.html

- ↑ http://www.napolun.com/mirror/napoleonistyka.atspace.com/battle_of_corunna.htm#britishadvance

- ↑ http://www.napolun.com/mirror/napoleonistyka.atspace.com/battle_of_corunna.htm

- ↑ http://www.napolun.com/mirror/napoleonistyka.atspace.com/battle_of_corunna.htm#battlecorunna2

- ↑ Wellington’s Dispatches, Volume III (Cambridge Library Edition); p. 378

- ↑ Wellington’s Dispatches, Volume III (Cambridge Library Edition); p. 375

- ↑ Julian Rathbone - Wellington's War, p. 146

- ↑ William Grattan - Adventures with the Connaught Rangers, Volume 1, p. 95

- ↑ Grattan, p. 100

- ↑ Grattan, p. 101

- ↑ Longford, p.254

- ↑ http://www.britishbattles.com/peninsula/fuentes.htm